Pakistan Supreme Court’s dubious ruling on Gilgit Baltistan is legally flawed

25-01-2019

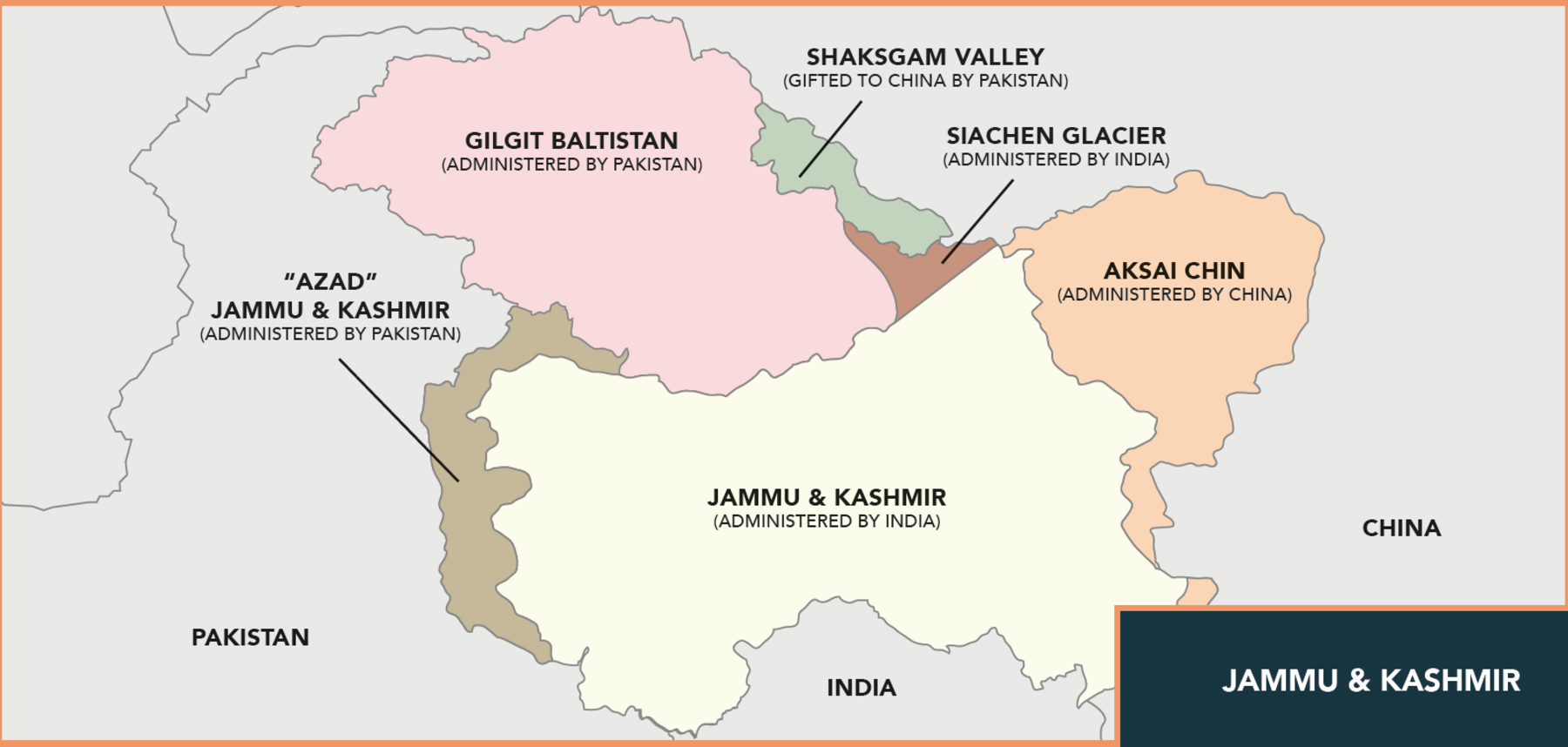

The ruling of the Pakistan Supreme Court on 17 January extending its jurisdiction to Gilgit Baltistan (GB), a region that is not lawfully a part of Pakistan but of the State of Jammu & Kashmir, is not legally tenable and threatens to further complicate resolution of the Jammu & Kashmir issue. It is not surprising, therefore, that the decision drew a sharp reaction from India, which has a legal claim to the erstwhile State of Jammu & Kashmir on the basis of the Instrument of Accession to India that was signed by Maharaja Hari Singh, the ruler of the princely State of Jammu & Kashmir, shortly after India gained independence from Great Britain in 1947. Equally anticipatable were the protests that the inhabitants of GB organized across Pakistan after the ruling was pronounced. The ruling also discomfited nationalists living on both sides of the Line of Control that presently divides Jammu & Kashmir between India and Pakistan.

A large seven-judge bench of the Pakistan Supreme Court headed by the outgoing Chief Justice Saqib Nisar had initially reserved its verdict on 7 January on a number of petitions challenging the Gilgit Baltistan Reforms Order 2018 and the Gilgit Baltistan Empowerment and Self Governance Order 2009. The petitioners had demanded the right for GB citizens to be governed through their own chosen representatives. As brought out in EFSAS Commentary of 01-06-2018, the Gilgit Baltistan Reforms Order 2018 had precipitated throes of protests last year against what was perceived by GB residents as the fortifying of Pakistan’s colonization of the region.

Subsequently, on 17 January, the Supreme Court pronounced its verdict which acknowledged that GB was a disputed territory and that the region’s status cannot be changed by the Pakistani government. GB would, accordingly, continue to remain administratively, not constitutionally, linked to Pakistan. GB’s disputed status, however, did not prevent the Supreme Court from extending its own jurisdiction over the region. Thus far, GB courts have been empowered to review the law-making done by the Gilgit Baltistan Council. These GB courts do not hold constitutional rights within Pakistan. This notwithstanding, the Supreme Court ruled that the people of GB would henceforth be able to challenge the appellate court’s decisions in the Supreme Court. A peculiar state of affairs has therefore been shaped by the Supreme Court in which the Pakistani executive has rightly been deemed as not having sovereign rights over GB, but the writ of another organ of the Pakistani State, its judiciary, has nevertheless been permitted to run large therein.

This dubious verdict of the Supreme Court has led to widespread disaffection among the people of GB, who are, in increasingly larger numbers, demanding an end to Pakistani rule in the region. A number of protest demonstrations against the ruling were held by GB residents on 20 January in Skardu, Islamabad and Karachi. They called for internal autonomy and pledged to oppose any executive order to govern GB. In Skardu, representatives of political parties, civil society organizations, religious bodies, and students gathered in large numbers at the historical ‘Yadgar-i-Shuhada’ monument and raised slogans against the Pakistani government. Local leaders Ghulam Mohammad, Shahzad Agha and Mohammad Ali Dilshad accused Pakistan of depriving the people of GB of their rights. Earlier, Gilgit Baltistan Youth Alliance (GBYA) leader Sheikh Hasan Johari was arrested under the trumped-up charge of creating hatred in Skardu while he was holding a protest against the Supreme Court ruling.

In Islamabad, a multi-party conference of GB residents was held with the specific purpose of developing consensus to initiate joint action against the verdict. The Leader of Opposition in the Gilgit Baltistan Legislative Assembly (GBLA), Captain (Retired) Shafi Khan, former chairman of Awami Action Committee GB, Maulana Sultan Raees, former member of the GBLA, Amina Ansari, Majlis-e-Wahdat-e-Muslimeen leader, Allama Syed Agha Ali Rizvi, Karakoram National Movement leader, Javed Hussain, retired Judge of the Supreme Appellate Court GB, Syed Jafar Shah, Gilgit Baltistan National Movement leader, Dr Ghulam Abbas, and other leaders and activists of the region participated. They issued a joint declaration after the conference that unanimously rejected the Pakistan Supreme Court’s ruling and resolved to launch a joint movement to ensure the rights of the people of GB. Underlining that the Supreme Court had categorically declared GB to be a disputed territory, the declaration stressed that it logically followed that the elected GBLA ought to be empowered to deal independently with all subjects barring foreign affairs, currency and defense. It also demanded a separate Supreme Court for GB. Importantly, it called for immediate cessation of harassment of political activists under the garb of the Fourth Schedule of the Anti-terrorism Act of Pakistan.

In Karachi, the GBYA organized a well-attended demonstration in front of the Karachi Press Club. GBYA rejected the Supreme Court ruling as one protecting oppressive governance by keeping the region’s populace unrepresented and disempowered. It demanded complete internal autonomy for GB, wherein all authority and legislative powers are transferred to an elected body that frames a separate constitution for the region. It also called for barring Pakistani political parties from operating in the region. Significantly, the GBYA came down heavily against Pakistan’s policy of engineering ‘demographic change’ in the region by pushing in settlers from Pakistani provinces, especially Punjab.

On the external front, India’s reaction to the Pakistan Supreme Court’s ruling was both prompt and stinging. The Indian Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) in a statement on 18 January informed that it had summoned the deputy High Commissioner of Pakistan and lodged a strong protest against the ruling. It conveyed unequivocally that the entire State of Jammu & Kashmir, which also includes 'Gilgit Baltistan', "has been, is and shall remain an integral part of India". It added that "Pakistan government or judiciary have no locus standi on territories illegally and forcibly occupied by it. Any action to alter the status of these occupied territories by Pakistan has no legal basis whatsoever". It further averred that "India rejected such continued attempts by Pakistan to bring material change in these occupied territories and to camouflage grave human rights violations, exploitation and sufferings of the people living there. Pakistan was asked to immediately vacate all areas under its illegal occupation”.

Pakistan has put itself on a slippery slope in GB. It recognizes the importance of retaining a minimum acceptable degree of separation from GB in furtherance of its broader policy on Jammu & Kashmir. Overtly integrating the region into Pakistan would not only take the wind out of the sails of Pakistan’s oft-repeated position favouring a plebiscite, but could also encourage India to do likewise with the part of Jammu & Kashmir that is administered by it. Legally too, Pakistan is on a weak footing on account of the Instrument of Accession to India. Additionally, the Pakistani government had earlier been counseled not only by the leadership of Pakistan Administered Jammu & Kashmir, but also by Pakistan’s proxies in Indian Administered Jammu & Kashmir, such as Hurriyat Conference leader Syed Ali Shah Geelani, against integrating GB with Pakistan. They had stressed that such integration would alter the contours of the Jammu & Kashmir-issue and impact adversely upon its resolution as GB was an integral part of the undivided princely State of Jammu & Kashmir. Geelani had termed any such move as “unacceptable”, and even went to the extent of saying that Islamabad lacked “constitutional and moral justification” to merge the region.

In recent years, however, a competing priority in the form of the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), which is seen by the Pakistani establishment as the magic wand that would wish away its economic woes, has complicated matters for Pakistan. GB, as Pakistan’s only geographical link to China, is vital for the CPEC. Under pressure from China on the nebulous status of the critical region, as also the frequency with which anti-Pakistan protests rear their unruly head in GB, Pakistan finds itself constrained to attempt to sneakily and incrementally alter this status. Each such attempt is, however, invariably and unsurprisingly sniffed out by the people of GB and agitated against. The Gilgit Baltistan Reforms Order 2018 and the recent Supreme Court ruling (which, incidentally, was the last judgment delivered by the outgoing Chief Justice Nisar), both constitute such attempts. Residents of GB rightly believe that when it comes to the CPEC or mega projects in GB such as the Diamer-Bhasha Dam, their land is, without their consent, considered to be a part of Pakistan. However, when it comes to their basic rights, it is conveniently projected as disputed.

Thrown repeatedly into the vortex of this vicious cycle, the people of GB have been at the receiving end of over 70 years of subjugation and uncertainty. Articulation of their legitimate grievances and demands has been reciprocated by the wrath of the Pakistani military establishment. Political activists are routinely detained on flimsy grounds, and disappearances are common. The media has been browbeaten into submission, and contrarian voices are denied vent. The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan has repeatedly highlighted the plight of GB residents and enjoined the Pakistani government to ensure their rights.

In these circumstances, the responsibility of international organizations, especially the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) that is mandated to look into such violations of human rights, cannot be overstated. In order to contribute towards the people of GB being given their rights, the UNHRC would require to move beyond the toothlessness it exposed in its first ever report on Jammu & Kashmir last year in which it skimmed over GB while hiding behind the pretext of the Pakistani government curtailing access to the region.

After all, Antía Mato Bouzas, the author of the study titled ‘Territorialisation, Ambivalence, and Representational Spaces in Gilgit-Baltistan’ for Leibniz-Zentrum Moderner Orient, Berlin, did succeed in gaining sufficient access to first-hand information in GB that enabled him to conclude that “In practice, however, the authoritarian side of the (Pakistani) state, vested in the military, has intervened significantly in border territories, mostly in Baltistan, and promoted an economy of dependence under the pretext of security. Moreover, in recent years, the construction and planning of major infrastructure projects in Gilgit-Baltistan have further highlighted the larger geo-strategic importance of the area. These interventions are focused on the creation and growth of connections with Pakistan and China. They promote new representations of space that are detached from the Kashmir conflict...”.